The Brandeis School of San Francisco is an inclusive and creative 60-year-old K-8 Jewish day school of 350 students, steeped in the progressive values and inventive approaches to Jewish practice that define San Francisco. In the school’s last strategic plan, the community articulated a vision of being a “future-focused” school. Today, with the process of writing a new strategic plan on the horizon, Dan, a ninth-year head of school, found himself wondering if his leadership team and board of trustees would benefit from learning how to think about the future, rather than simply assuming it was something we all know how to do.

- Home

- HaYidion: The Prizmah Journal

- AI and Tech

- Wrestling With the Future, With Curiosity and Empathy

Wrestling With the Future, With Curiosity and Empathy

Luckily, the Bay Area is a place where wrestling with the future is a daily practice as commonplace as the self-driving cars on our streets. Dan reached out to Ariel, who works at the K12 Lab at the Hasso Plattner School of Design (d.school) at Stanford University. Ariel was part of the team offering a keynote address at this year’s Prizmah Conference, about educators as futurists. He and Dan had connected as part of Brandeis’s Ethical Creativity Institute, where he helped design and teach a program on ethics and design to Jewish day school educators from around the world. Given Ariel’s experience building frameworks to help schools confront the future, Dan was inspired to reach out to engage Ariel in working with the Brandeis community.

The question Dan had for Ariel was simple: As Brandeis prepares to lay the groundwork for its next 60 years, can you teach our leaders what it takes to imagine new futures?

Ariel and his team at the d.school had developed a project to equip schools with the methodology and mindsets of futurism, a disparate field that brings together art, music and science fiction with mathematical modeling. Drawing from the work of their colleague Lisa Kay Solomon, the d.school team developed a framework called Five Approaches for Futures Thinking to assist schools in navigating uncertainty with their communities. Influenced by the d.school project, Ariel worked with Dan to design and develop new tools for which Brandeis, a unique Jewish school in a unique context, could engage with its community and imagine new futures.

In this article, we will share a selection of futures-thinking strategies, all of which were brought to bear during two retreats that we co-designed and ran in summer 2023: one with the Brandeis senior leadership team, and one with the school’s board of trustees.

To paraphrase Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert, pondering the future is a uniquely human activity. But one need not look far back in history to notice the limitation of our capacity to ward off existential threats. By using strategies from futurism, we can improve our capacity to imagine, anticipate and react to downstream changes, creating resilient and bold organizations.

Thinking in Images

At Brandeis, we began by introducing the concept of an Image of the Future. Such images are all around us—think of dystopian films like The Matrix or Terminator series, novels like The Giver by Lois Lowry, or the techno-optimistic billboards lining the freeways of San Francisco. Humans shape these images, and in turn these images shape us, reflecting our expectations, hopes and anxieties back to us in a coherent narrative.

The pull toward images can be of great service to leaders. Note that a common organizational tendency is to think of the future in abstract rhetoric and phrases (“aiming for student belonging”) that are amorphous and unlikely to translate into real-life action. Management research suggests that using images instead (“a smile on every student’s face”) can provide motivation as well as organizational clarity (for more, see How Can Leaders Overcome the Blurry Vision Bias?). When examined under these terms, the ultimate task of the strategic plan is to craft a compelling image of the future that includes and inspires our community.

As part of a retreat focused on futures thinking, we made space with the senior leadership team at Brandeis to look through specific images of the future (from The Jetsons to Gattaca) and discuss what they might have to say about our own practices around teaching and learning, or building community. The practical matter is to first learn to recognize and decode visions from the future, and later generate images for your school. You’ll begin to spot these in your everyday life—including those that influence education—and chart a course for your school with its own compelling vision.

Exploring Before Deciding

For most of us, the future holds a heavy burden, the place where we dump our fears or aspirations. As such, it can be difficult to explore with curiosity or dispassion. Yet if we are to accept the fact that the future is uncertain, we must equip our minds with a certain openness to explore a multitude of possibilities. Note how this can run afoul of more traditional strategic-planning processes, which require school leadership to think technically in three- to five-year increments.

The first question Ariel posed to the board came from future forecaster Jane McGonigal: “If the future is a time when many or most things in your life will be different from what they are today, how long from now does that future start?” While answers vary, the debrief pointed us to a simple lesson: If we want to move beyond the preconceived notions baked into the present moment, we need to think far ahead, typically 10 years away.

This concept that McGonigal describes as time spaciousness points to a tension at the heart of strategic planning itself: Where strategy requires spaciousness to explore a broad landscape, planning is often practical and detail-oriented. With Brandeis, we chose to start with a wider time horizon before committing to the technical project of preparing the strategic plan.

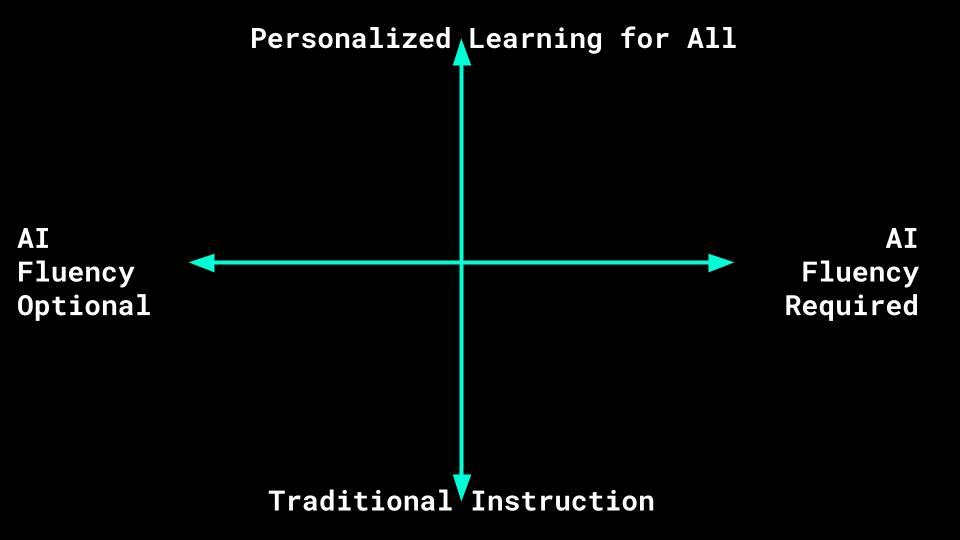

To imagine and explore possible futures, we use a deceptively simple 2 x 2 grid where we chart uncertainties on two axes to create four scenarios. Using this tool, we can account for variables outside of education, like the effect of Artificial Intelligence on the job market, and explore its impact on our sphere of education from the outside-in.

Here too there is a strong human tendency to navigate to pre-conceived narratives. The trick is to defer any selection about which possibilities we prefer, believe are likely, would like to avoid or otherwise react strongly to on first impression. Heeding the plural in Futures Thinking, Ariel reminds participants to allow ourselves to remain open to many outcomes. More importantly, each possibility offers a speculative perspective from which school leadership teams and boards can evaluate risks, rehearse adaptations and in so doing create a state of readiness.

In one instance, a group of trustees charted a 2 x 2 with “AI in Employment” against “Personalized Learning.” The group decided that the top-right quadrant, with both of those uncertainties becoming stronger, was a scenario in which AI fluency had become a basic requirement for employment (much like, say, email in the present), and all learning had become individualized. Suddenly, rather than worrying over the fate of the essay in assessment, for example, this group was wrestling in detail with big questions about what the future of school could be.

Empathy for the Future

A final tool we have to break against the abstraction of the future is empathy. Said simply, the future will have people in it, individuals that we care about—including our own potential descendants. By projecting our empathy across time, we can better connect with all those in future generations, and imagine how our actions today can influence and improve the lives of their present(s).

Ariel invited the Brandeis community to practice this unique strategy by imagining a child three generations from today. What would they look like? How would they dress? Where would they live? What would they care about? How would they relate to Judaism? As the details came into focus, participants were invited to realize that person by constructing a picture.

This tool invites both school leaders and trustees to think about the future of their own families or communities and center on their aspirations for those future beings. Both of us being former classroom teachers, we also appreciate the change in modalities it offers, inviting participants to “think with their hands” as they craft and collage.

—

Schools are fundamentally concerned with the future, believing as we do that the efforts we take with young people today can help them imagine new possibilities for the world they will later inhabit as workers, community members, parents and leaders. Despite that orientation toward optimism, we often engage in the work of envisioning what’s to come without taking the time to learn tools to build our own proficiency as future thinkers.

These retreats have launched the leadership—lay and professional—at The Brandeis School of San Francisco into its upcoming strategic planning work with a new sense of agency. Engaging with these tools has allowed us to think beyond the prescribed units determined by the school day, week, semester and year—beyond ourselves, in fact.

Rather than engaging with the future as a singular extension of the present or as an undefined threat, we are thinking in detail and with our fuller faculties (empathy, curiosity) about the many possible futures ahead and how Brandeis will continue to thrive in a multitude of scenarios. This has taken the form of broadening the scope of Jewish identities and Jewish-adjacent communities we imagine being part of those futures in enrollment planning, considering the role of remote schooling in the context of wildfires and other climate crises in risk-management work, and a hevrutah pair on AI in education between the director of technology and making at Brandeis and the head of school—which included pushing all leadership team members to figure out how generative AI can help them do their work.